Federal Data in the Crosshairs

What's at Stake for Public Safety?

August 2025

By Amy Solomon, MPP, and Betsy Pearl, MA, Council on Criminal Justice

Key Takeaways

- Timely and trustworthy federal data is essential to effective policy and practice at all levels of government.

- Threats to statistical collections undermine the nation’s ability to monitor crime and victimization and pursue evidence-driven policies for protecting public safety, particularly among vulnerable groups.

- Since January 2025, federal agencies have deleted—and sporadically restored—thousands of datasets and other resources from government websites, including data on public health and safety. Such disruptions to federal statistical activity imperil public trust in federal data and information.

- Eliminated resources from the Department of Justice include a database of federal law enforcement officer misconduct, data on gender identity of people in federal prisons, and statistics on racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system.

- Federal data infrastructure has been chronically underfunded, politically vulnerable, and technologically outdated for years. Without stronger safeguards, it will remain exposed.

Introduction

The recent firing of the nation’s Bureau of Labor Statistics commissioner has brought unprecedented public attention to the integrity of federal statistical collections, an essential but often overlooked function of the United States government. Federal agencies maintain about 315,000 datasets that span nearly every aspect of American life, ranging from public school performance and housing affordability to agricultural production, food prices, highway conditions, and aviation accidents.1

Public officials at all levels of government look to these data to guide choices about resource allocation, policy priorities, and day-to-day operations. Federal statistics are of substantial value to people outside government as well. With access to timely and trustworthy federal data, researchers can track trends and identify evidence-driven solutions, and advocates can hold leaders accountable for better outcomes.

Much of the nation’s data on public safety and health comes from the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which collectively maintain thousands of datasets tracking indicators of Americans’ safety and well-being.2 DOJ is home to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), which is the country’s primary source of criminal justice statistics and administers about 50 different collections on crime victimization and justice system operations.3 National-level crime statistics come from DOJ’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which also collects data related to law enforcement officer safety and use-of-force.4

At HHS, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) operates databases that track non-fatal and fatal injuries, including those involving firearms or violence, as well as indicators of risky behavior leading to death or injury among young people.5 HHS also collects a range of measures of behavioral health through its Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Taken together, these sources of federal data provide essential insights into the nature of public health and safety in the U. S., laying the groundwork for data-driven solutions to some of the country’s most pressing challenges.

Yet federal statistics are both a “valuable and vulnerable” asset, as former U.S. Chief Data Scientist Denice Ross put it.6 The federal data infrastructure has come under particular scrutiny in recent months, as actions undertaken by the Trump administration jeopardize the accessibility and quality of some federal data, including information used to guide public safety and health practices nationwide.

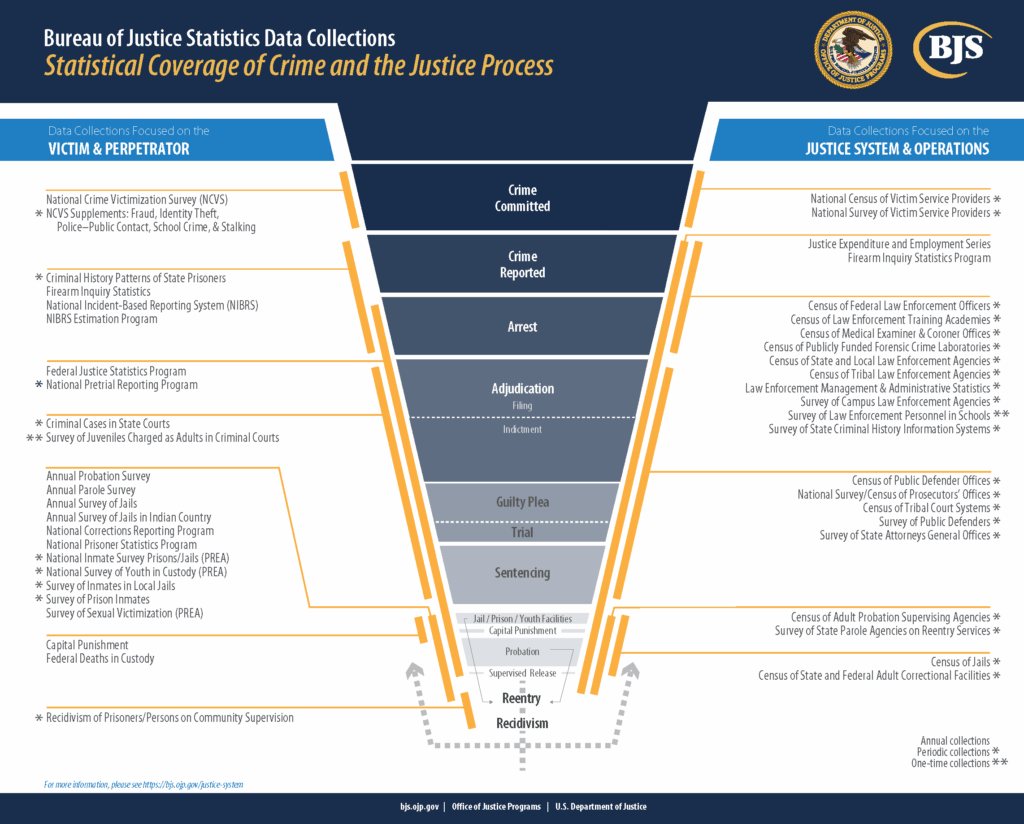

Figure 1. BJS Statistical Coverage of Crime and the Justice Process

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (n.d.) BJS Statistical Coverage of Crime and the Justice Process.

Threats to Federal Public Safety and Public Health Data

What's Been Cut and Altered

In early 2025, thousands of web pages disappeared from federal government websites following directives from the White House to remove references to gender in federal materials and discontinue diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts.7 To be sure, incoming administrations of both parties revamp federal websites to better align with their priorities. The “digital transition” has become a part of the modern transfer of power from one White House to the next. For example, when President Biden took office in 2021, federal websites replaced certain terminology that was favored by the Trump administration with language that reflected the Biden administration’s values and vision, just as the Trump administration did in 2017 when assuming office after the Obama administration.8

Federal data and statistics, however, are expected to operate above the political fray—and have largely succeeded in the past.9 Yet in 2025, some 3,000 datasets were among the content deleted by federal agencies in response to White House direction.10 HHS, for example, removed data used to monitor and identify emerging trends in adolescent health and well-being, including measures of substance use and mental health, exposure to community violence, and other risky behaviors or experiences that threaten youth health and safety.11 HHS restored this dataset, which is disaggregated by gender, and many others following a court order in February 2025.12 The webpage now includes a statement on the deletion and court-ordered reinstatement of the data, expressing the White House’s stance that any information “promoting gender ideology is extremely inaccurate” and concluding that the “page does not reflect biological reality and therefore the Administration and this Department rejects it.”13

Researchers have identified more than 100 public health datasets that have been altered since January 2025, most of which were modified to remove references to gender in accordance with White House directives.14 In most instances, the federal government did not publicly document the changes made to these datasets, undermining both scientific knowledge and trust in the integrity of federal datasets.15

Police Misconduct

The deletion of data compromises efforts to promote transparency and accountability within the justice system. In January 2025, DOJ decommissioned the National Law Enforcement Accountability Database, a repository of federal law enforcement officer misconduct records used by agency hiring personnel to assess the suitability of job candidates.16 In a statement about the database’s deactivation, the administration said that “the Biden executive order creating this database was full of woke, anti-police concepts that make communities less safe like a call for ‘equitable’ policing and addressing ‘systemic racism in our criminal justice system.’”17

Launched in December 2023, this database in fact has bipartisan origins, as its creation was mandated by a 2020 executive order from President Trump and a 2022 executive order from President Biden.18 By September 2024, 94 federal law enforcement agencies had submitted 4,790 records of officer misconduct dating back to 2018.19 The database was the only centralized online repository of federal law enforcement officer misconduct, and was used nearly 10,000 times in its first eight months to screen candidates for federal policing positions.20 Its removal reopens the door for agencies to unknowingly hire officers with records of excessive force, corruption, or abuse, jeopardizing the safety of the public and integrity of the policing profession.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Like HHS, DOJ has also removed and later restored some online resources. In early 2025, DOJ deleted a statistical brief and dataset from the BJS that presented findings from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) on violent victimization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people.21 Months later, the brief was reposted on the BJS website.

Other DOJ resources were taken down and remain inaccessible. For example, the Bureau of Prisons deleted statistics on the gender identity of individuals in federal prisons, which had indicated that about 2,200 incarcerated people identified as transgender.22 While this is a small percentage of the roughly 150,000 individuals in federal prison, transgender people are disproportionately victimized while incarcerated.23 Roughly 40% of incarcerated transgender adults experienced sexual abuse in prison in 2011-2012, the most recent year for which data was available, compared to 4% of the overall prison population.24

Changes to future federal surveys will further obscure trends in violence against transgender people, in particular. BJS has removed questions about gender identity from several25 upcoming data collections, including the NCVS.26 Previous data from this survey has shown that transgender individuals face violent victimization rates 2.5 times higher than their cisgender counterparts.27 BJS also plans to stop collecting information on gender as part of the Survey of Sexual Victimization, which tracks incidents of sexual abuse in adult and juvenile correctional facilities.28 Likewise, HHS will no longer collect information on the gender identity of victims of homicide, suicide, and other violent fatalities as part of its National Violent Death Reporting system.29

Moving forward, survey data will no longer provide policymakers and advocates with the information they need to detect and address elevated rates of victimization among vulnerable gender groups, putting safety at risk.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities

In early 2025, DOJ deleted national juvenile justice statistics that allowed for analyses of racial and ethnic disparities in the processing of delinquency cases.30 The data, published by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, shed light on the levels of disparity introduced at various decision points within the juvenile justice system, from the time a young person is referred to the court through the final disposition of their case. An analysis of data from 2020 found that across offense types, cases involving White youth were the most likely to be diverted and the least likely to result in detention pending case disposition.31 Once adjudicated, cases involving White youth were less likely to result in out-of-home placement than cases involving Black or Hispanic youth, regardless of offense category.32 With the deletion of these statistics, national and state-level officials have lost an important benchmark for assessing trends in juvenile justice systems and facilitating fairer and more effective treatment of young people.

Terrorism and Mass Violence

Other data has disappeared from non-governmental sources that relied on federal funding that has recently been withdrawn. This includes the Terrorism and Targeted Violence (T2V) Database, administered by the University of Maryland with funding from the Department of Homeland Security. The department terminated funding for T2V in March 2025, effectively shutting down the only publicly available source of information on attempted and successful acts of terrorism and targeted violence in the U.S.33 Before its funding was eliminated, T2V was a source of actionable insights into the evolving nature of mass violence, terrorism, hate crimes, school and workplace violence, and other targeted attacks across the country. Data showed that these deadly incidents were on the rise in early 2025, and with the elimination of T2V, it is increasingly difficult to identify data-driven strategies to prevent them.34 T2V is now exploring a commercial model, which would restrict access to users with paid data licenses, in order to resume operations in the future.35

Other Federal Resources

The threats to both public trust and effective policymaking are compounded by the disappearance of other information from federal websites. For example, DOJ has blocked public access to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service, one of the world’s largest online libraries of criminal justice research.36 DOJ also took down the Violent Crime Reduction Roadmap, a clearinghouse of violence reduction resources organized around the action steps identified by experts in a Council on Criminal Justice (CCJ) report, Ten Essential Actions Cities Can Take to Reduce Violence Now.37

Other deleted DOJ materials include research and recommendations for upholding the constitutional right to counsel in juvenile delinquency cases;38 guidance for serving justice-involved veterans39 and preventing the spread of communicable diseases40 in correctional facilities; resources for understanding and preventing bullying and youth hate crimes;41 a study that finds lower rates of arrest among undocumented immigrants than native-born U.S. citizens;42 and more. Although it is difficult to track the full scope of knowledge that has been disrupted across the federal government’s sprawling network of websites, some researchers and other stakeholders have been able to download and preserve federal resources for future public use, protecting valuable information from deletion or manipulation.43 Some 1,100 datasets are now available through the Data Rescue Project, a clearinghouse of preserved government resources launched by data and information stakeholder groups in February 2025.44

What to Watch For

Resources that remain publicly accessible will become obsolete if data collections are not updated on a regular basis. The administration has announced plans to discontinue at least five surveys administered by the U.S. Census Bureau, which collects information on behalf of other federal agencies such as BJS.45

BJS Data Collections

Media reporting suggests that the eliminated collections may include the BJS Survey of Local Jail Inmates, which is the nation’s only source of detailed information on the characteristics of local jail populations and includes background on the nature of individuals’ arrest, their use of substances or firearms prior to jail admission, and the health care and other services they receive while incarcerated.46 The survey offers actionable insights into the drivers of incarceration and strategies to improve safety and health outcomes for the millions of people who cycle through America’s jails each year.47

The impact to this survey and other BJS data collections remains to be seen. But in one promising development, BJS has continued to release new statistical products on a regular basis, publishing six new reports in July 2025 alone.48 The agency also continues to publish an annual schedule for its statistical releases, previewing the types of data the public can expect to see throughout the year.49 Moving forward, stakeholders should look out for changes to or deviations from this publication calendar, which may signal disruptions in BJS’s planned statistical activities.

Political leadership can also shape the future of the bureau and its products. The White House has yet to name a BJS director, a politically appointed role that should be held by a qualified statistical expert. Likewise, the administration has not nominated an assistant attorney general for the Office of Justice Programs (OJP), the Senate-confirmed DOJ official who directly oversees BJS. Any nominee for that post should be evaluated on their commitment to respecting and advocating for the statistical integrity and maximum independence for BJS.

Public Health Data

Other longstanding data collections have been disrupted by significant reductions in staffing at federal agencies such as the CDC, which leads national disease surveillance and prevention efforts through investigations, data analysis, and other activities. As a result of substantial personnel cuts, the CDC terminated a partnership with the federal Consumer Product Safety Commission to collect data on nonfatal injuries resulting from adverse drug effects, alcohol, motor vehicle and aircraft accidents, and other incidents.50 The CDC also plans to discontinue the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, which was designed to maximize reliable reporting of these forms of victimization to improve prevention and response efforts.51 Media reporting indicates that the office responsible for this public health survey was hard hit by layoffs in early 2025.52

Resource cuts have also affected statistical activity at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which gathers statistics for HHS on a range of important health measures. In June 2025, SAMHSA discontinued the Drug Abuse Warning Network, a source of timely data on emergency department visits related to substance use.53 The network’s termination means the nation has lost an early warning system for identifying novel psychoactive substances and emerging trends in substance use across the country. SAMHSA also laid off teams of federal experts responsible for public health data collections such as the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which has tracked behavioral health trends in the U.S. for more than 50 years.54 HHS released new findings from the survey in July 2025, with a note that the agency has worked with contractors to continue data collection and analysis.55 Implications for the survey and data are uncertain.

Deaths in Custody

In addition to eliminating a range of statistical resources, federal resource cuts have created threats to the accuracy and completeness of certain data collections. In April 2025, the administration terminated 373 grants from OJP worth a combined $820 million.56 Among the terminated grants was funding for the improvement of state-level data collection and compliance with the Death in Custody Reporting Act, a federal law that was enacted with bipartisan support and requires states to collect and report information to DOJ on any death that occurs in law enforcement and correctional custody.57

Obtaining complete and accurate data on deaths in custody is an essential first step to understanding the nature of the problem and developing solutions to reduce future fatalities. Yet state authorities have long struggled to collect and consolidate key information from local justice system agencies, leading to significant gaps in the data reported to the federal government.58 In recognition of these challenges, during the Biden administration, OJP invested in training and technical assistance to help states address shortcomings in the collection and reporting of data on deaths in custody, with the goal of improving the quality and completeness of national information on such fatalities.59 At the same time, OJP’s Bureau of Justice Assistance sought to increase transparency around deaths in custody by publishing national-level data submitted by states for the first time in November 2024, followed by state-level data in early January 2025.60 The termination of the technical assistance to help states improve data collection will exacerbate longstanding concerns about the federal government’s ability to obtain—and eventually publish—a full and accurate picture of deaths in custody, and to identify data-driven strategies for preventing loss of life.

General Erosion in Public Trust

Additional concerns about data quality stem from the erosion of trust in the federal government. The quality of federal survey data is predicated on the public’s willingness to provide the government with honest and complete information, often on sensitive or personal topics. Distrust in government may deter participation in federal data collections, an issue raised by government agencies themselves. In 2019, the U.S. Census Bureau published an analysis of survey data that identified distrust in government, data privacy concerns, and fear of repercussions as key barriers to participation in the 2020 decennial census.61 The analysis found that roughly one-quarter of respondents expressed concern about the confidentiality of their responses to the 2020 census, and a similar proportion feared that the Census Bureau would share their data with other federal agencies or that their answers would be used against them.62

In March 2025, the White House moved to reduce restrictions on sharing data across federal agencies, bringing renewed attention to issues surrounding data collection and privacy.63 In the face of mounting public concern about federal privacy protections and the misuse of personal information, federal agencies may struggle to collect the reliable data necessary to guide policymaking.

Declining participation already poses a challenge to key sources of public safety data, such as BJS’s NCVS. In 2023, the overall response rate for NCVS was around 54%, down from 88% in 2013.64 The 2023 response rate did not meet the 60% threshold established by the Census Bureau, below which there may be issues with data quality.65 BJS acknowledged that low response rates introduce “potential bias in the NCVS estimates,” and applied weighted adjustments to the estimates to mitigate and correct for these issues.66

Modernizing Public Safety Data

Threats to existing and future statistical collections undermine the nation’s ability to monitor crime and victimization and pursue evidence-driven policies for protecting public safety. Yet any future efforts to restore and strengthen federal statistics must go beyond simply returning to the status quo. In particular, the nation’s public safety data infrastructure is persistently underfunded and well overdue for modernization.

Despite the breadth of its statistical mandate, BJS receives relatively little funding from Congress. An independent analysis by the American Statistical Association concluded that BJS faces the most severe resource constraints of all 13 of the federal government’s principal statistical agencies.67 The BJS budget is far lower than that of many of its counterparts and dropped from $67.6 million in FY 2018 to $58.8 million in FY 2024, amounting to a 29% reduction in purchasing power when adjusting for inflation.68

Figure 2. Annual Budgets of Federal Statistical Agencies

Crime Statistics

BJS’s budgetary challenges have impacted its most prominent data collection, the NCVS, one of the two primary measures of crime in the country. The yearly survey measures Americans’ experiences with victimization, including incidents that were not reported to the police, while the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program captures the number of crimes recorded by law enforcement agencies nationwide.69

In FY 2024, the cost of administering NCVS exceeded BJS’s entire budget from Congress for the year.70 Although Congress generally allows OJP to reserve a small percentage of other budget line items to supplement research and statistical activities, financial constraints have limited BJS’s ability to update the NCVS survey design and implement new features, and have necessitated periodic reductions in sample size.71

Underfunding has impacted BJS’s other statistical activities as well. Although the NCVS is an annual collection, many of the bureau’s other surveys are administered on a periodic basis. But with budget shortfalls, some surveys have become less and less frequent, with years—or even decades—elapsing between data collections. The most recent BJS data on jail population characteristics, for example, dates back to 2002, while statistics on pretrial release and detention have not been updated since 2009.72 Plans are underway at BJS to collect and publish new data on these topics, although it remains to be seen whether cuts to federal surveys will impact ongoing collections.73

Figure 3. Periodic BJS Data Collections by Year

Sources: Please see endnote74

Once data is collected, BJS must clean, weight, analyze, and verify the data, a labor-intensive process that the agency estimates can take up to two years to complete.75 In the case of NCVS, findings are generally released between 10 and 12 months after the data collection concludes. Additional resources could enhance the timeliness of such releases, enhancing the data’s utility and value to the decision-makers responsible for shaping public safety policy, practice, and resource allocation.

The FBI’s UCR program struggles with similar challenges around timeliness. The FBI generally publishes crime statistics once a year, with a 9- to 10-month lag.76 This year, the FBI released annual crime data for 2024 in August 2025, about a month earlier than is typical.77 Although the FBI has made efforts to release quarterly data in recent years, the availability of this data has been inconsistent, with the last quarterly publication in September 2024.78 In the absence of regular and timely federal statistics, public officials must make consequential decision about their public safety agenda without a clear and complete picture of the national landscape.

In recognition of this gap, in April 2023 CCJ convened a working group of consumers and producers of criminal justice statistics, including some of the foremost researchers and practitioners from across academia, advocacy, law enforcement, government, and the public health sector.79 Working in consultation with representatives of the FBI and BJS, the group produced a series of actionable recommendations for strengthening the nation’s crime data infrastructure and better equipping policymakers with timely, accurate, and usable data.80

In the year since the panel released its recommendations, federal officials have demonstrated interest in pursuing some elements of the roadmap. In October 2024, FBI officials confirmed plans to transition to monthly crime data reporting in the future, a key recommendation from the working group.81 And in a recent executive order, the White House called for increased “investment in and collection, distribution, and uniformity of crime data across jurisdictions,” a directive aligned with the working group’s recommendations for enhanced funding for crime data infrastructure.82 The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 also recognized the importance of trustworthy federal crime data, deeming the NCVS “of particular importance” and calling on DOJ to “prioritize and sufficiently fund it.”83

Despite these promising signals, the federal government has yet to implement meaningful improvements to its crime statistics program. In the meantime, researchers from CCJ and other private sector entities have stepped in to fill gaps in the crime data landscape.84 CCJ publishes timely analyses of crime trends in the U.S. at both the midpoint and end of each calendar year. The most recent report, released in July 2025, found that homicide and other violent crimes continued to decline during the first six months of the year.85

Implications and Conclusion

Federal statistical agencies tend to fly under the public radar, but surveys show that Americans recognize the value of the data that their government collects. More than two-thirds of Americans believe that federal statistics are important for understanding society and helping public officials make good decisions, according to a June 2025 survey.86 The vast majority—over 70% of Republicans and Democrats alike—believe that the collection of federal statistics should continue to be conducted without regard to politics.87

Federal data collections are an invaluable, and increasingly vulnerable, resource for public safety. Although the challenges associated with crime statistics long predate the current administration, recent federal actions—including the high-profile dismissal of the Senate-confirmed Bureau of Labor Statistics commissioner—have heightened the urgency of concerns. The erosion of the data infrastructure isn’t just an academic or bureaucratic distress. It hinders effective policymaking, erodes trust in government, and undercuts Americans’ ability to evaluate the performance of their leaders.

When it comes to protecting the federal statistics, it’s not enough to return to the pre-2025 status quo. The path forward requires:

- Statutory protections to prevent the deletion or alteration of federal datasets without public notice and independent review;

- Robust funding for the Bureau of Justice Statistics, FBI Uniform Crime Reporting, and other core statistical programs from the CDC, SAMHSA, and other federal agencies;

- Investments in independent archiving initiatives led by universities and nonprofits to preserve public datasets against loss or manipulation;

- Modernization of data reporting systems to ensure data is released quickly, at regular intervals, and in formats usable by policymakers, researchers, and the public; and

- Strengthened protections for federal statistical agencies’ autonomy and independence from political influence.

Federal data infrastructure has been chronically underfunded, politically exposed, and technologically outdated for years. Without stronger safeguards, it will remain at the mercy of political winds.

Acknowledgements

Amy L. Solomon is a senior fellow at the Council on Criminal Justice and former assistant attorney general at the U.S. Department of Justice. Her expertise spans federal justice funding, criminal justice policy and administration, corrections and reentry reform, and the use of research and data to advance community safety.

Betsy Pearl is a policy consultant with the Council on Criminal Justice and previously served at the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs as deputy chief of staff and senior adviser to the assistant attorney general. Her expertise includes federal criminal justice policy, justice grantmaking, and community-centered approaches to public safety and reform.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Thaddeus Johnson and Alexis Piquero for their expert guidance and insightful contributions to this report. Additional thanks to Brian Edsall, Erik Opsal, and Rachel Yen for their support in the design and communications efforts for this report.

This report was produced with support from The Just Trust, Public Welfare Foundation, and Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies, as well as the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Southern Company Foundation, and other CCJ general operating contributors.

About Justice in Perspective

Justice in Perspective is a nonpartisan series examining the complexities of federal justice funding, policy, research, and operations. It is led by CCJ Senior Fellow Amy L. Solomon, former assistant attorney general in charge of the Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs.

Suggested Citation

Solomon, A., & Pearl, B. (2025). Federal data in the crosshairs: What’s at stake for public safety? Council on Criminal Justice. https://counciloncj.org/federal-data-in-the-crosshairs-whats-at-stake-for-public-safety/

Endnotes

1 As of August 12, 2025, the Data.gov data catalog includes 315,991 datasets from federal government sources. See General Services Administration. (n.d.) Data.gov Data Catalog [Dataset]. https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/?q=&organization_type=Federal+Government

2 As of August 12, 2025, the Data.gov data catalog includes 1,425 datasets from the Department of Justice and 7,538 datasets from the Department of Health and Human Services. See General Services Administration. (n.d.) Data.gov Data Catalog.

3 American Statistical Association & George Mason University. (2024). The Nation’s Data at Risk: Supporting Materials – Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://www.amstat.org/docs/default-source/amstat-documents/the-nation’s-data-at-risk-supporting-materials/bureau-of-justice-statistics.pdf; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (n.d.) About BJS. https://bjs.ojp.gov/about

4 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. (n.d.) Crime/Law Enforcement Stats (Uniform Crime Reporting Program). https://www.fbi.gov/how-we-can-help-you/more-fbi-services-and-information/ucr

5 CDC WISQARS – Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting system. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, June 14). About YRBSS. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/about/index.html

6 Ross, D. (2025, June 20). The data we take for granted: telling the story of how federal data benefits American lives and livelihoods. Federation of American Scientists. https://fas.org/publication/the-data-we-take-for-granted/

7 Jingnan, H., & Lawrence, Q. (2025, March 19). Here are all the ways people are disappearing from government websites. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/03/19/nx-s1-5317567/federal-websites-lgbtq-diversity-erased; Palmer, K. (2025, June 10). Preserving the federal data Trump is trying to purge. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/government/science-research-policy/2025/06/10/preserving-federal-data-trump-trying-purge; Singer, E. (2025, February 2). Thousands of U.S. government web pages have been taken down since Friday. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/02/upshot/trump-government-websites-missing-pages.html

8 The White House website, in particular, tends to undergo an overhaul, with new administrations bringing their own branding and priorities to the site. For example, the Obama White House website included pages focused on climate change and civil rights that were not retained by the incoming Trump Administration, while the Trump Administration featured content from the President’s 1776 Commission that was not included on the new Biden White House website. The National Archives has preserved a copy of each outgoing administration’s website since the White House established an online presence in 1994, providing ongoing public access to these records. See Balk, T. (2025, January 20). The White House website got a quick Trump makeover. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/20/us/politics/white-house-website-trump.html; Davenport, C. (2017, January 20). With Trump in charge, climate change references purged from website. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/20/us/politics/trump-white-house-website.html; Kurtzleben, D. (2020, January 17). Digital transition of power is not so peaceful. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2017/01/20/510847064/digital-transition-of-power-is-not-so-peaceful; Mufson, S. & Dennis, B. (2017, January 20). On White House website, Obama climate priorities vanish, replaced by Trump’s focus on energy production. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/energy-environment/wp/2017/01/20/on-white-house-website-obama-climate-priorities-vanish/; Pietsch, B. (2021, January 20). The Biden administration quickly revamped the White House website. Here’s how. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/20/us/politics/biden-white-house-website.html; Ross, J. (2017, January 20). Civil rights page also deleted from White House website. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/2017/live-updates/politics/live-coverage-of-trumps-inauguration/civil-rights-page-also-deleted-from-white-house-website/. Shear, M.D. (2021, February 24). The words that are in and out with the Biden Administration. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/24/us/politics/language-government-biden-trump.html

9 In an assessment of risks to federal statistical agencies, the American Statistical Association cites several examples of ”undue political interference or meddling” in statistical activity over the past 20 years, but notes that incidents of a serious magnitude are ”relatively rare.” See American Statistical Association & George Mason University. (2024a). The nation’s data at risk. https://www.amstat.org/docs/default-source/amstat-documents/the-nation’s-data-at-risk—report.pdf?v=0321

10 Palmer, 2025.

11 Cox, C., Rae, M., Kates, J., Wager, E., Ortaliza, J., & Dawson, L. (2025, February 2). A look at federal health data taken offline. KFF. https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/a-look-at-federal-health-data-taken-offline/

12 Stone, W. (2025, February 11). Judge orders restoration of federal health websites. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/shots-health-news/2025/02/11/nx-s1-5293387/judge-orders-cdc-fda-hhs-websites-restored

13 Restored HHS websites include the following statement, “Per a court order, HHS is required to restore this website as of 11:59PM ET, February 11, 2025. Any information on this page promoting gender ideology is extremely inaccurate and disconnected from the immutable biological reality that there are two sexes, male and female. The Trump Administration rejects gender ideology and condemns the harms it causes to children, by promoting their chemical and surgical mutilation, and to women, by depriving them of their dignity, safety, well-being, and opportunities. This page does not reflect biological reality and therefore the Administration and this Department rejects it.” See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance System (YRBSS). https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/index.html

14 Freilich, J., & Kesselheim, A. S. (2025). Data manipulation within the US Federal Government. The Lancet, 406(10500), 227–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(25)01249-8

15 Freilich & Kesselheim, 2025.

16 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2024, December). National Law Enforcement Accountability Database. https://bjs.ojp.gov/national-law-enforcement-accountability-database

17 Jackman, D. & Dwoskin, E. (2025, February 21). Justice Department deletes database tracking federal police misconduct. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2025/02/20/trump-justice-nlead-database-deleted/

18 Executive Order 13929, 85 FR 37325 (2020). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-06-19/pdf/2020-13449.pdf; Executive Order 14074, 87 FR 32945 (2022) https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-05-31/pdf/2022-11810.pdf.

19 Hyland, S. (2024). National Law Enforcement Accountability Database, 2018–2023 (NCJ 309614). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/nlead1823.pdf

20 The equivalent database for state and local law enforcement agencies, known as the National Decertification Index (NDI), remains accessible. Operated by the International Association of Directors of Law Enforcement Standards and Training (IADLEST), NDI receives but is not reliant upon federal resources, and remains available for use by law enforcement hiring officials. See: Kaste, M. (2025, February 28). Trump took down police misconduct database, but states can still share background check info. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/02/28/nx-s1-5305281/trump-police-misconduct-database-background-checks

21 The BJS statistical brief, entitled Violent Victimization by Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, 2017–2020, was originally published in June 2022. Users access the brief and underlying data tables by navigating to a landing page that includes links to download the relevant files. Based on a review of archived content from the Wayback Machine, BJS blocked access to the landing page for this brief in February 2025. It is unclear when the landing page came back online; it was unavailable as of the most recent capture from the Wayback Machine on May 25, 2025. The link to download the the brief was inaccessible as of July 19, 2025, the most recent capture from the Wayback Machine. On July 29, 2025, BJS republished the brief under a different URL, accessible from the restored landing page. To access the landing page, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2022, June 21). Violent Victimization by Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, 2017–2020. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/violent-victimization-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity-2017-2020. To access an archived version of the published statistical brief, see: Truman, J. L., & Morgan, R. E. (2022). Violent victimization by sexual orientation and gender identity, 2017–2020 (NCJ 304277). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Archived January 7, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250107021701/https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/vvsogi1720.pdf

22 Diaz, J. (2025, January 30). Trans community fears Trump’s actions will upend legal precedent on prison protections. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/01/30/nx-s1-5277164/trump-executive-order-trans-inmates; Johnson, C. (2025, January 31). Health info wiped from federal websites following Trump order targeting transgender rights. PBS News. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/health-info-wiped-from-federal-websites-following-trump-order-targeting-transgender-rights

23 Schwartz, M., Harmon, A., Dewan, S., & Thrush, G. (2025, February 21). Prison officials detail treatment of trans inmates under Trump gender order. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/21/us/trump-trans-women-prison.html

24 Beck, A. J. (2014). Supplemental tables: Prevalence of sexual victimization among transgender adult inmates. In Sexual Victimization in Prisons and Jails Reported by Inmates, 2011–12 (NCJ 241399). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/svpjri1112_st.pdf; Beck, A. J., Berzofsky, M., Caspar, R., & Krebs, C. (2013). Sexual victimization in prisons and jails reported by inmates, 2011–12 (NCJ 241399). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/svpjri1112.pdf

25 As of August 2025, BJS has removed gender identity variables from at least five surveys: the Juvenile Facility Census Program, the National Crime Victimization Survey, the School Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey, the Survey of Inmates in Local Jails, and the Survey of Sexual Victimization. See Information Collection Review Data on Reginfo.gov. (n.d.). Office of Management and Budget, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/jsp/PRA/ICR_info.myjsp

26 Morgan, R.E. (2025, March 3). Memorandum to the Office of the Chief Statistician regarding non-substantive change request for the National Crime Victimization Survey (OMB Control No. 1121-0111). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/DownloadDocument?objectID=153624701; Office of Management and Budget, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. (2025). Information Collection Request Reference No. 202503-1121-001. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/PRAViewICR?ref_nbr=202503-1121-001#

27 Truman, J. L., & Morgan, R. E. (2022). Violent victimization by sexual orientation and gender identity, 2017–2020 (NCJ 304277). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/vvsogi1720.pdf

28 Kottke-Weaver, S. (2025, February 19). Memorandum to the Office of the Chief Statistician regarding nonsubstantive change notification for the Survey of Sexual Victimization: OMB Control No. 1121-0292. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/DownloadDocument?objectID=152587901; Office of Management and Budget, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. (2025a). Information Collection Request Reference No. 202502-1121-003. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/PRAViewICR?ref_nbr=202502-1121-003

29 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025, February 28). Non-substantive change request, OMB Control Number 0920-0670, the National Violent Death Reporting System. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/DownloadDocument?objectID=153865401; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025a, April 18). Non-substantive change request, OMB Control Number 0920-0670, the National Violent Death Reporting System. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/DownloadDocument?objectID=158687001; Office of Management and Budget, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. (2025b). Information Collection Request Reference No. 202503-0920-009. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/PRAViewICR?ref_nbr=202503-0920-009

30 National Racial and Ethnic Disparities (R/ED) Databook. (2023). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice And Delinquency Prevention. Archived January 14, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250114130345/https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/statistical-briefing-book/data-analysis-tools/r-ed-databook

31 U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (2023). Racial and ethnic disparities in the processing of delinquency cases, 2020. Archived November 29, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20241129091216/https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/publications/data-snapshot-racial-ethnic-disparities-processing-delinquency-cases-2020.pdf

32 U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice And Delinquency Prevention, 2023

33 Statement on the cancellation of T2V. (2025, March 25). National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. https://www.start.umd.edu/news/statement-cancellation-t2v

34 Statement on the cancellation of T2V, 2025.

35 Pate, A. (2025, May 6). Letter from the Director. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. https://www.start.umd.edu/news/letter-director

36 National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS) Virtual Library. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Archived January 8, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250108170358/https:/www.ojp.gov/ncjrs-virtual-library

37 U.S. Department of Justice. (2023, December 11). Justice Department announces release of Violent Crime Reduction [Press release]. https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-release-violent-crime-reduction-roadmap; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance. (2024, August 8). Violent Crime Reduction Roadmap. Archived January 18, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250118014415/https://bja.ojp.gov/violent-crime-reduction-roadmap/intro

38 Development Services Group, Inc. (2018). Indigent defense for juveniles. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Archived December 13, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20241213002352/https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/model-programs-guide/literature-reviews/indigent_defense_for_juveniles.pdf

39 U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections. (n.d.). Justice-involved veterans. Archived on January 14, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250114192352/https://nicic.gov/resources/resources-topics-and-roles/topics/justice-involved-veterans

40 U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections. (n.d.-a). Communicable diseases in correctional facilities. Archived on January 14, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250114192222/https://nicic.gov/resources/resources-topics-and-roles/topics/communicable-diseases-correctional-facilities

41 U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (2022, February). Hate crimes and youth. Archived January 16, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250116090920/https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/model-programs-guide/literature-reviews/hate-crimes-and-youth#9-0; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (n.d.). Preventing Youth Hate Crimes & Indentity-Based Bullying Initiative. Archived January 10, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250110164815/https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/programs/preventing-youth-hate-crimes-bullying-initiative.

42 U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. (2024). Undocument immigrant offending rate lower than U.S.-born citizen rate. Archived January 18, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250118140931/https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/undocumented-immigrant-offending-rate-lower-us-born-citizen-rate#1-0

43 Gaffney, A. (2025, March 21). Government science data may soon be hidden. They’re racing to copy it. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/21/climate/government-websites-climate-environment-data.html; Mulligan, S.J. (2025, February 7). Inside the race to archive the US government’s websites. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2025/02/07/1111328/inside-the-race-to-archive-the-us-governments-websites/; Palmer, 2025; Satter, R. (2025, February 6). Harvard law library acts to preserve government data amid sweeping purges. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/harvard-law-library-acts-preserve-government-data-amid-sweeping-purges-2025-02-06/

44 Data Rescue Project. (2025). Data Rescue Project launches new portal. https://www.datarescueproject.org/data-rescue-project-portal/; Data Rescue Project (2025a). About Data Rescue Project. https://www.datarescueproject.org/about-data-rescue-project/

45 Lo Wang, H. (2025, May 23). DOGE created a “survey of surveys” for a push to cut some government data collection. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/05/23/nx-s1-5409331/doge-data-census-bureau

46 Schneider, M. (2025, May 23). DOGE targets Census Bureau, worrying data users about health of US data infrastructure. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/census-bureau-doge-federal-surveys-fe560e377be69e913660a6d90c1ee419

47 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2024a). 2024 Survey of Inmates in Local Jails. https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/SILJ_flyer24-3.18.2024.pdf

48 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2025, August 5). July 2025 Month in review. https://bjs.ojp.gov/month-review/july-2025-month-review

49 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2024b, December 31). Forthcoming publications. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/forthcoming

50 Douglas, L. (2025, April 16). US consumer safety agency to stop collecting swaths of data after CDC cuts. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/us-consumer-safety-agency-stop-collecting-swaths-data-after-cdc-cuts-2025-04-16/

51 In March 2025, HHS’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) submitted a memo regarding the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey to the Office of Management and Budget, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs that states, “NCIPC intends to Discontinue this data collection.” The memo requests approval to change to the status of the survey collection, a step that would allow NCIPC to move forward with discontinuing the survey. See: Office of Management and Budget, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Information Collection Request Reference No. 202503-0920-002. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/PRAViewICR?ref_nbr=202503-0920-002; Zirger, J.M. (2025). Non-substantive change request, [NCIPC] the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS), OMB Control No. 0920-0822. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/DownloadDocument?objectID=153643501

52 Ollstein, A. M. (2025, April 13). ‘We are flying blind’: RFK Jr.’s cuts halt data collection on abortion, cancer, HIV and more. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2025/04/13/abortions-cancer-in-firefighters-and-super-gonorrhea-rfk-jr-s-cuts-halt-data-collection-00284828

53 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (n.d.). Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN). https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/dawn-drug-abuse-warning-network

54 Chatterjee, R. (2025, May 29). They’ve tracked Americans’ drug use for decades. Trump and RFK Jr. fired them. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/shots-health-news/2025/05/29/nx-s1-5407849/samhsa-nsduh-trump-rfk-jr-hhs-cuts. Gordon, E., & Ovalle, D. (2025, June 19). SAMHSA has fought drug and mental health crises. Now it’s in crisis. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2025/06/19/samhsa-addiction-mental-health-cuts/

55 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (n.d.-a). 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) releases: Frequently asked questions. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health/national-releases#frequently-asked-questions

56 Solomon, A. & Pearl, B. (2025). DOJ funding update: A deeper look at the cuts. Council on Criminal Justice. https://counciloncj.org/doj-funding-update-a-deeper-look-at-the-cuts/

57 Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2013. 34 U.S.C. 60105 (2014) https://www.congress.gov/113/statute/STATUTE-128/STATUTE-128-Pg2860.pdf

58 Janovsky, D. (2024) How states are (and aren’t) collecting death-in-custody data. Project on Government Oversight. https://www.pogo.org/analysis/how-states-are-and-arent-collecting-death-in-custody-data; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance. (2023). Death in Custody Reporting Act: State convening summary report. https://bja.ojp.gov/doc/dcra-state-convening-summary-report.pdf; U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2022). Deaths in custody: Additional action needed to help ensure data collected by DOJ are utilized (GAO-22-106033). https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-106033

59 Justice Information Resource Network. (n.d.). Death in Custody Reporting Act (DCRA) Training and Technical Assistance Center (TTAC). https://jirn.org/our-work/our-projects/dcra-tta/; Solomon, A. (2024, May 23). Taking action to reduce deaths in custody. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. https://www.ojp.gov/archive/news/ojp-blogs/safe-communities/inside-perspectives/taking-action-to-reduce-deaths-in-custody

60 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance. (2024, November 15). Death in Custody Reporting Act (DCRA) data collection: State reported deaths in custody interactive tables. https://bja.ojp.gov/program/dcra/reported-data

61 McGeeney, K., Kriz, B., Mullenax, S., Kail, L., Walejko, G., Vines, M., Bates, N., & Garcia Trejo, Y. (2019). 2020 Census barriers, attitudes, and motivators study survey report. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/program-management/final-analysis-reports/2020-report-cbams-study-survey.pdf

62 McGeeney, Kriz, Mullenax, Kail, Walejko, Vines, Bates, & Garcia Trejo, 2019.

63 Badger, E. & Frenkel, S. (2025, April 9). Trump wants to merge government data. Here are 314 things it might know about you. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/09/us/politics/trump-musk-data-access.html; Huot-Marchand, A. (2025, June 25). Trump knocks down barriers around personal data, raising alarm. The Hill. https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/5366922-trump-data-sharing-privacy-surveillance/; Joffe-Block, J. (2025, June 24). The Trump administration is making an unprecedented reach for data held by states. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/06/24/nx-s1-5423604/trump-doge-data-states; Pell, S.K., Stewart, J. & Tanner, B. (2025). Privacy under siege: DOGE’s one big, beautiful database. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/privacy-under-siege-doges-one-big-beautiful-database/

64 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2014) National Crime Victimization Survey technical documentation (NCJ 247252). https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/ncvstd13.pdf; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2024c). National Crime Victimization Survey, [United States], 2023: User guide (ICPSR 38962). Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NACJD/studies/38962/versions/V1/datadocumentation#

65 U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.) Quality standards metrics definitions. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/methodology/sample-size-and-data-quality/quality-standards-metrics-definitions.html; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2024c

66 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2024c.

67 The American Statistical Association assessed the resources, professional autonomy, and parent agency support available to the principal federal statistical agencies using a 5-point rating scale: weak (1), challenging (2), mixed (3), good (4), and strong (5). BJS was the only agency to receive a “weak” rating in the assessment of resources. See American Statistical Association & George Mason University, 2024a.

68 To measure purchasing power, the American Statistical Association used the GDP price deflator to account for inflation. In inflation-adjusted FY2009 dollars, the BJS FY 2018 budget was $58.5 million (FY09 $) and the BJS FY2024 budget was $41.3 million (FY09 $). See American Statistical Association & George Mason University, 2024a; Pierson, S. (n.d.). Federal Statistical Agencies – budgets since FY00. American Statistical Association. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1_xt8oI2neZyTwaZvtyQOtujzuHnjemZPwPuYVsEELr0/.

69 Lauritsen, J. & Lopez, L. (2025). When crime statistics diverge: Understanding the two major sources of crime data in the U.S. Council on Criminal Justice. https://counciloncj.org/when-crime-statistics-diverge/

70 American Statistical Association & George Mason University, 2024.

71 American Statistical Association & George Mason University, 2024; National Research Council. (2008). Surveying victims: Options for conducting the National Crime Victimization Survey (R. Groves & D. Cork, Eds.). National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12090

72 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (2009, May 26). State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS) and National Pretrial Reporting Program (NPRP). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/state-court-processing-statistics-scps-and-national-pretrial-reporting-program-nprp; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (2009a, May 26) Survey of Inmates in Local Jails (SILJ). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/survey-inmates-local-jails-silj.

73 BJS materials state that data collection for the Survey of Inmates in Local Jails “will likely occur in selected jails between Nocember 2024 and February 2025.” The BJS website does not include further updates on the collection status. Per BJS’s website, the National Pretrial Reporting Program was relaunched in 2021. As of August 2025, the BJS website lists NPRP as “currently in the field,” although the website also states that the collection is “expected to conclude in late 2024.” See U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2024a; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2009

74 For Survey of Inmates in Local Jails, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2009a. For Criminal History Patterns of Prisoners, see: Durose, M.R., Snyder, H.N., & Cooper, A.D. (2015). Multistate Criminal History Patterns of Prisoners Released in 30 States. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/multistate-criminal-history-patterns-prisoners-released-30-states. For Census of Adult Parole Supervising Agencies, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009b, October 26). Census of Adult Parole Supervising Agencies. https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/census-adult-parole-supervising-agencies. For State Court Processing Statistics and National Pretrial Reporting Program, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2009. For Recidivism of State Prisoners, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009c, May 26). Recidivism of State Prisoners. https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/recidivism-state-prisoners. For National Inmate Survey Jails/Prisons, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009d, May 26). National Inmate Survey. https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/national-inmate-survey-nis#2-0. For Census of Public Defenders/Indigent Defense, see: Adams, B., Hussemann, J., Hall, H., Lyon, J., Friess, K., Davies, A., Scott, K., & Strong, S. (2024). Survey of Public Defenders (SPD) pilot report (NCJ 308967). https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/spdpr.pdf. For National Survey/Census of Tribal Court Systems, see: NORC at the University of Chicago. (n.d.). Census of Tribal Court Systems. https://www.norc.org/research/projects/census-of-tribal-court-systems.html; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2021, July 28). National Survey of Tribal Court Systems (NSTCS). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/national-survey-tribal-court-systems-nstcs. For Survey of Prison Inmates, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2019, January 8). Survey of Prison Inmates. https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/survey-prison-inmates-spi. For National Census of Victim Service Providers, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2023, August 16). 2023 National Census of Victim Service Providers (NCVSP). https://bjs.ojp.gov/2023-national-census-victim-service-providers-ncvsp; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2019, November 12). National Census of Victim Service Providers. https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/ncvsp. For NCVS Fraud Supplement, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2021a, May 28). Supplemental Fraud Survey (SFS). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/supplemental-fraud-survey-sfs. For Census of State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009e, May 18). Census of State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies (CSLLEA). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/census-state-and-local-law-enforcement-agencies-csllea; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2024b. For Census of Medical Examiner and Coroner Offices, see: Census of Medical Examiner and Coroner Offices. (n.d.). RTI International. https://bjscmec.rti.org; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009f, May 26). Census of Medical Examiner and Coroner (ME/C) Offices. https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/census-medical-examiner-and-coroner-mec-offices. For Survey of State Attorneys General Offices, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2020, May 11). Survey of State Attorneys General Offices (SSAGO). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/survey-state-attorneys-general-offices-ssago. For National Survey of Youth in Custody, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009g, July 7). National Survey of Youth in Custody (NSYC). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/national-survey-youth-custody-nsyc. For Census of Jails, see: BJS Census of Jails: Frequently asked questions. (n.d.). RTI International. https://jailcensus.rti.org/Home/FAQ. For Census of State and Federal Adult Correctional Facilities, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009h, May 22). Census of State and Federal Adult Correctional Facilities (CCF, Formerly CSFACF). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/census-state-and-federal-adult-correctional-facilities-ccf-formerly-csfacf; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2024b. For NCVS Stalking Supplement, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2021b, May 28). Supplemental Victimization Survey (SVS). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/supplemental-victimization-survey-svs. For Census of Tribal Law Enforcement Agencies, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2023a, July 25). Census of Tribal Law Enforcement Agencies (CTLEA). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/census-tribal-law-enforcement-agencies-ctlea; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2025a). 2025 Census of Tribal Law Enforcement Agencies. NORC at the University of Chicago. https://www.norc.org/content/dam/norc-org/pdf2025/2025-census-of-tribal-law-enforcement-agencies-project-summary.pdf. For National Survey of Victim Service Providers, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2019, November 19). National Survey of Victim Service Providers (NSVSP). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/national-survey-victim-service-providers-nsvsp. For Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009i, May 18). Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/law-enforcement-management-and-administrative-statistics-lemas. For National Survey/Census of Prosecutors Offices, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009j, May 26). National Survey of Prosecutors (NSP). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/national-survey-prosecutors-nsp; Urban Institute. (2024, April 10). Urban Institute to collect data for Bureau of Justice Statistics National Census of Prosecutor Offices. https://www.urban.org/alerts/urban-institute-collect-data-bureau-justice-statistics-national-census-prosecutor-offices. For Census of Federal Law Enforcement Officers, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009k, May 26). Census of Federal Law Enforcement Officers (CFLEO). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/census-federal-law-enforcement-officers-cfleo. For Census of Publicly Funded Forensic Crime Laboratories, see: Census of Publicly Funded Forensic Crime Laboratories. (n.d.). RTI International. https://bjsforensics.org/; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009l, May 15). Census of Publicly Funded Forensic Crime Laboratories (CPFFCL). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/census-publicly-funded-forensic-crime-laboratories-cpffcl. For NCVS Identity Theft Supplement, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2021c, May 28). Identity Theft Supplement (ITS). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/identity-theft-supplement-its. For NCVS School Crime Supplement, see: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). School Crime Supplement (SCS) to the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). https://nces.ed.gov/programs/crime/scs/; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2021d, May 28). School Crime Supplement (SCS). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/school-crime-supplement-scs. For Survey of State Criminal History Information Systems, see: SEARCH. (n.d.). Survey of State Criminal History Information Systems. https://www.search.org/resources/surveys/. For Survey of Campus Law Enforcement Agencies, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009m, May 18). Survey of Campus Law Enforcement Agencies (SCLEA). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/survey-campus-law-enforcement-agencies-sclea. For NCVS Police-Public Contact Supplement, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009n, May 18). Police-Public Contact Survey (PPCS). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/police-public-contact-survey-ppcs#1-0. For Census of Law Enforcement Training Academies, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2009o, May 26). Census of Law Enforcement Training Academies (CLETA). https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/census-law-enforcement-training-academies-cleta.

75 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2021e, May 12). Data collection process. https://bjs.ojp.gov/data/data-collection-process

76 Council on Criminal Justice. (2024). Better crime data, better policy. https://www.counciloncj.org/crime-trends-working-group/final-report/executive-summary

77 Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Information Services Division. (2025, August 5). FBI releases 2024 reported crimes in the nation statistics [Press release]. https://www.fbi.gov/news/press-releases/fbi-releases-2024-reported-crimes-in-the-nation-statistics

78 Asher, J. (2025, March 17). The FBI stopped publishing quarterly data, Here’s what’s next. Jeff-alytics. https://jasher.substack.com/p/the-fbi-stopped-publishing-quarterly; Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Information Services Division. (2024, September 30). FBI releases 2024 Quarterly Crime Report and Use-of-Force Data Update [Press release]. https://www.fbi.gov/news/press-releases/fbi-releases-2024-quarterly-crime-report-and-use-of-force-data-update-q2; Hanson, E.J. (2022). NIBRS participation rates and federal crime data quality (IN11936). Congressional Research Service. https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IN11936

79 Council on Criminal Justice, 2024.

80 Council on Criminal Justice, 2024.

81 Levenson, E. (2024, October 26). The FBI releases crime stats months after the fact. This new crime tracker is trying to be more timely – and the FBI is too. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2024/10/26/us/crime-stats-delay-fbi

82 Executive Order 14288, 90 FR 18765 (2025). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2025-05-02/pdf/2025-07790.pdf

83 “The National Crime Victimization Survey, which is the nation’s largest crime survey and predates the BJS (it dates to the Nixon Administration), is of particular importance, and the department should prioritize and sufficiently fund it. This survey provides the only comprehensive and credible alternative to police reports for showing who commits crimes.” See Hamilton, G. (2023). Department of Justice. In P. Dans & S. Groves (Eds.), Mandate for Leadership: the Conservative Promise (p. 572). The Heritage Foundation. https://static.heritage.org/project2025/2025_MandateForLeadership_FULL.pdf

84 Other non-governmental efforts to track crime trends include the Real-Time Crime Index, NORC’s Live Crime Tracker, the Major Cities Chiefs Association, and the Gun Violence Archive.

85 Lopez, E. & Boxerman, B. (2025). Crime trends in U.S. cites: Mid-year 2025 update. Council on Criminal Justice. https://counciloncj.org/crime-trends-in-u-s-cities-mid-year-2025-update/

86 SSRS. (2025, June 23). The public’s views on the value of federal statistics. https://ssrs.com/insights/the-publics-views-on-the-value-of-federal-statistics/

87 SSRS, 2025.