Outcomes from a Jail-Based Veterans Housing Unit

August 2025

By Lina Cook, MS, Sandy Felkey Mullins, JD, Josh Doerner, MA, Marlee Sherrod, MS, and Angela Hawken, PhD, New York University

Veterans housing units are specialized quarters offered to incarcerated military veterans in both jails and prisons. Typically accompanied by supplementary programs, these units may be peer-led or run by trained staff or volunteers with a military background and are designed to address the unique needs of veterans experiencing incarceration, offering them tailored services along with rehabilitation and reintegration support. The first unit opened in 1987 in Wilton, New York, at the Mt. McGregor Correctional Facility. In 2024, the National Institute of Corrections listed 105 veterans housing units in jails and prisons across the United States.1

To be eligible for veterans housing units, incarcerated people typically must verify their military service, either formally (providing military record, verifying through online systems) or informally (self-reporting military service). Although specific components vary, most programs serve only men, as few female veterans are incarcerated in most correctional facilities.

Veterans housing units have not been evaluated for long-term effectiveness to assess whether they help participants succeed during reentry and desist from further criminal behavior. This report seeks to partially fill that gap using data on veterans who participated in the Veterans Housing Unit (VHU) in a large county jail, and veterans who were booked into the jail but not referred for VHU participation.

Key Takeaways

- Veterans housing units in correctional facilities are designed to address the unique needs of incarcerated veterans by offering tailored rehabilitation programs, services, and reintegration support.

- Veterans housing units typically serve men, and program components vary widely. Eligibility requirements, beyond the verification of military service through official records or self-reporting, may include a review of the seriousness of criminal charges, disciplinary records, and behavioral health status, as well as an interview to assess “fit.”

- There were no statistically significant differences in two-year post-release return-to-jail outcomes between veterans who participated in a jail-based veterans housing unit and those who did not, after accounting for factors such as age, offense security, and mental health and/or substance use disorder diagnoses.

- Few veterans units have been evaluated for long-term effectiveness to assess whether they help participants succeed during reentry or provide other benefits. More research is needed to determine the impact of these programs.

The Veterans Housing Unit

In 2016, a large county jail in one northeastern state launched a veteran housing unit (VHU). The unit is designed to support reentry by combining treatment programs and guest speakers with the camaraderie of shared military experience to address underlying challenges. Jail administrators screen all new admissions for military service using the Veteran Reentry Search Service (VRSS), an online system managed by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Only individuals verified through VRSS are eligible for placement in the unit.

Potential participants are further screened to ensure that they understand the expectations of the unit and are a good fit for participation based on their medical and mental health needs, a review of their current charges and criminal history, and an assessment of any disciplinary infractions. The VHU is available to eligible veterans who are being held pretrial and those serving jail sentences.

Differences Between VHU Participants and Other Veterans in the Jail

This study focuses on the 231 people booked into the jail for either sentencing or bail and who were identified as veterans between July 2016 and September 2021. When looking only at the first booking for each individual in this time frame, 148 participated in the VHU and 83 did not. The comparison between participants and non-participants examined whether those veterans who participated in the VHU differed in key ways from those who were deemed ineligible by jail staff or who were otherwise not referred for VHU participation. There were no statistically significant differences in race/ethnicity or length of stay in the jail between participants and non-participants. However, there were statistically significant differences in age at release, diagnosed behavioral health disorder (defined as a diagnosed mental health and/or substance use disorder), and severity of offense2 between VHU participants and non-participants. See Table 1 for a more detailed breakdown of the variables used in the study comparison.

Table 1. Characteristics of Veterans, by VHU Participation

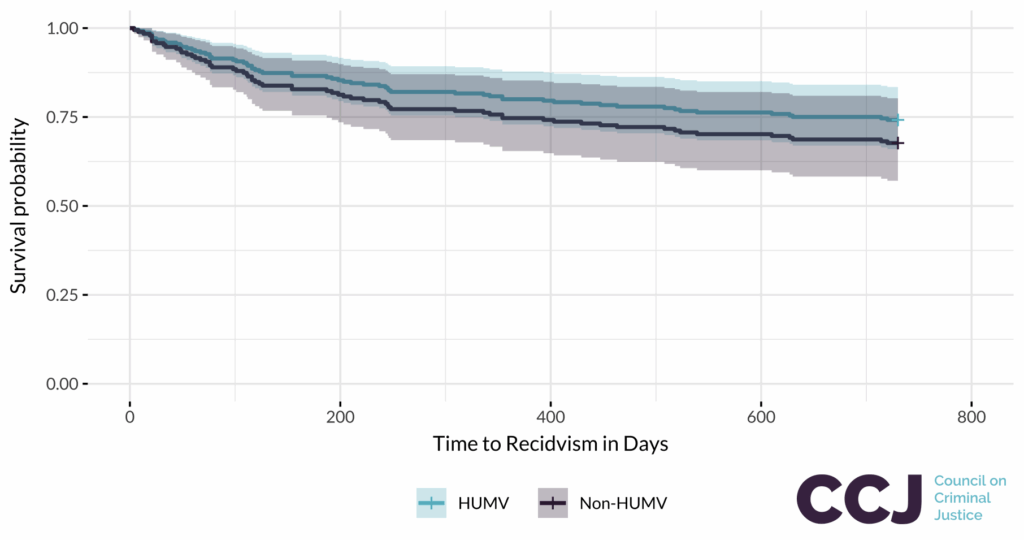

Differences in Recidivism Outcomes for VHU Participants Were Not Statistically Significant

To explore the effectiveness of the VHU program, the study used a survival analysis to examine the impact of participation on two outcomes: two-year post-release recidivism (defined as return to custody at the jail) and the number of days veterans remained in the community before being rebooked.

The study controlled for the three factors that differed significantly between veterans who participated in the VHU and those who did not: age at release, behavioral health diagnosis, and severity of offense. After controlling for these differences, VHU participants were somewhat less likely to return to jail, though the difference was not statistically significant.

As shown in Table 2, the odds ratio associated with VHU participation was 0.765, indicating that veterans who participated in the VHU were roughly 23% less likely to be rebooked in the jail. However, because this result was not statistically significant, it should be interpreted as suggestive rather than conclusive.

Table 2. Two-Year Recidivism Risk Factors (Cox Survival Model Results)

Although there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups on recidivism, VHU participants spent about a week longer, on average, in the community before recidivating (594 days to rebooking in the jail for VHU participants compared to 587 days to rebooking for other veterans in the jail).

Figure 1. Estimated Time to Recidivism Over Two Years (Cox Survival Curve)

Discussion and Implications

While there is a lack of rigorous evidence related to the impact of veterans housing units on recidivism, correctional administrators generally support them. Unlike veterans treatment courts, specialized veterans housing units lack formal standards guiding their structure, screening, or programming, likely due to limited research. This lack of standardization may contribute to wide variation in how units are implemented and the outcomes they produce, making it difficult to assess effectiveness or replicate promising models. Importantly, one evaluation of one program should not be interpreted as a final verdict on whether veterans housing units “work” more broadly; their impact may depend heavily on design, delivery, and local context.

In addition, admission to these units is often subjective, influenced by factors such as behavior, mental health, and criminal history. These factors can introduce selection bias and make it difficult to isolate the effects of the unit itself. A clearer understanding of who is admitted, who is excluded, and what services participants actually receive would strengthen any evaluation of outcomes.

Recidivism was the only available outcome measure for this study’s evaluation, and it was narrowly defined as rebooking into the jail. Broader indicators—such as post-release housing, employment, and service engagement—would offer a more complete view of the short- and long-term effects of veterans housing units. It is also unclear whether these units aim primarily to reduce recidivism or to serve other purposes, such as honoring military service, reinforcing veterans’ identity, or improving behavior during custody.

There are no cost estimates associated with veterans housing units, and their benefits likely vary by facility. Understanding their value requires clarity about their goals, standardized eligibility and operation measures, and better documentation of the range of services delivered. More research is needed, beginning with a clear definition of the intended purpose of these units. Aligning investment with public value depends on whether these specialized units and their associated programs consistently improve recidivism and other outcomes without diverting resources from higher-need veterans.

About the Authors

Lina Cook, MS, is an assistant research scientist in the Litmus program at the Marron Institute of Urban Management at New York University. As a statistician, she primarily uses data to generate numbers and metrics to inform the work that is being done in the social justice realm.

Sandy Felkey Mullins, JD, is a senior research scholar in the Litmus program at the Marron Institute of Urban Management at New York University, where she assists public safety-related agencies and organizations serving people who have been involved with the criminal justice system in collaboratively designing and implementing reforms.

Josh Doerner, MA, is an assistant research scholar at the Marron Institute of Urban Management at New York University. Previously, Doerner was a program development specialist at the Illinois Department of Corrections.

Marlee Sherrod, MS, is a research specialist in the Office of Academic Research, Evaluation, and Data Analytics at The City University of New York. Prior to this role, Sherrod was a research fellow at the Marron Institute of Urban Management at New York University.

Angela Hawken, PhD, is the former director of the Marron Institute of Urban Management at New York University, where she was also professor of public policy. She is now a member of the founding faculty and vice dean for research at the School of Government and Policy at Johns Hopkins University.

Acknowledgements

Stephanie Kennedy contributed to this report, along with former staffers Kathy Sanchez, Aaron Rosenthal, and Jim Seward, as well as other members of the Council team.

Support for the Veterans Justice Commission comes from Bank of America, The Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation, Craig Newmark Philanthropies, The Just Trust, LinkedIn, the National Football League, T. Denny Sanford, the Wilf Family Foundation, and May & Stanley Smith Charitable Trust, as well as the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Southern Company Foundation, #StartSmall, and other CCJ general operating contributors.

Suggested Citation

Cook, L., Mullins, S. F., Doerner, J., Sherrod, M., & Hawken, A. (2025). Outcomes from a jail-based veterans housing unit. Council on Criminal Justice. https://counciloncj.org/outcomes-from-a-jail-based-veterans-housing-unit/

Endnotes

1 National Institute of Corrections Justice Involved Facilities Map. https://dev-nicic.zaidev.net/microsites/justice-involved-veterans/justice-involved-veterans/jiv-facilities-map (Please note that this resource is no longer available online.)

2 The state classifies offenses into nine levels based on their seriousness. Levels 1–4 (less serious offenses) include misdemeanors and low-level felonies such as disorderly conduct, trespassing, public intoxication, and nonviolent regulatory offenses like minor drug possession or low-value theft. Levels 5–9 (more serious offenses) cover more serious felonies, including unarmed robbery, aggravated assault, child exploitation offenses, drug trafficking, and violent crimes up to manslaughter and murder. See the supplemental methodology report for details.