At Second Meeting, Group Explores Current Drivers of Violent Crime Increase, Discusses Historical Context

At Second Meeting, Group Explores Current Drivers of Violent Crime Increase, Discusses Historical Context

At its second meeting, the Violent Crime Working Group discussed current trends in violent crime and identified the potential drivers that may be causing crime to spike. The discussion featured a presentation by Richard Rosenfeld, the Curators’ Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of Missouri–St. Louis and co-author of a recent Council report on crime trends. In addition, the Group discussed the broad, structural factors contributing to violent crime to help put current trends into context.

Trends in Violent Crime

Working group members explored current trends in violent crime and the leading explanations for those trends in an effort to gain a common understanding of the problem before turning to solutions. Here’s what we know.

What We Know

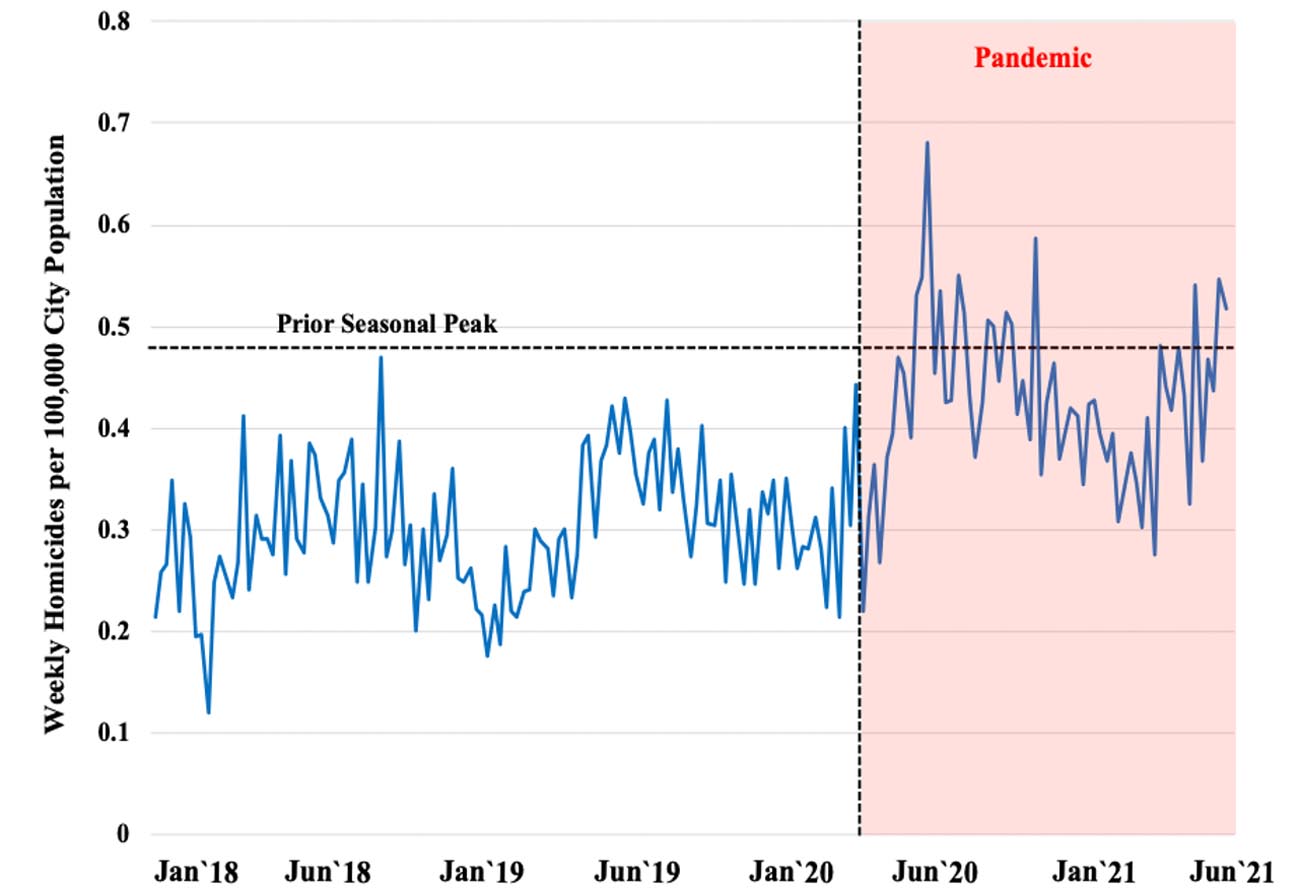

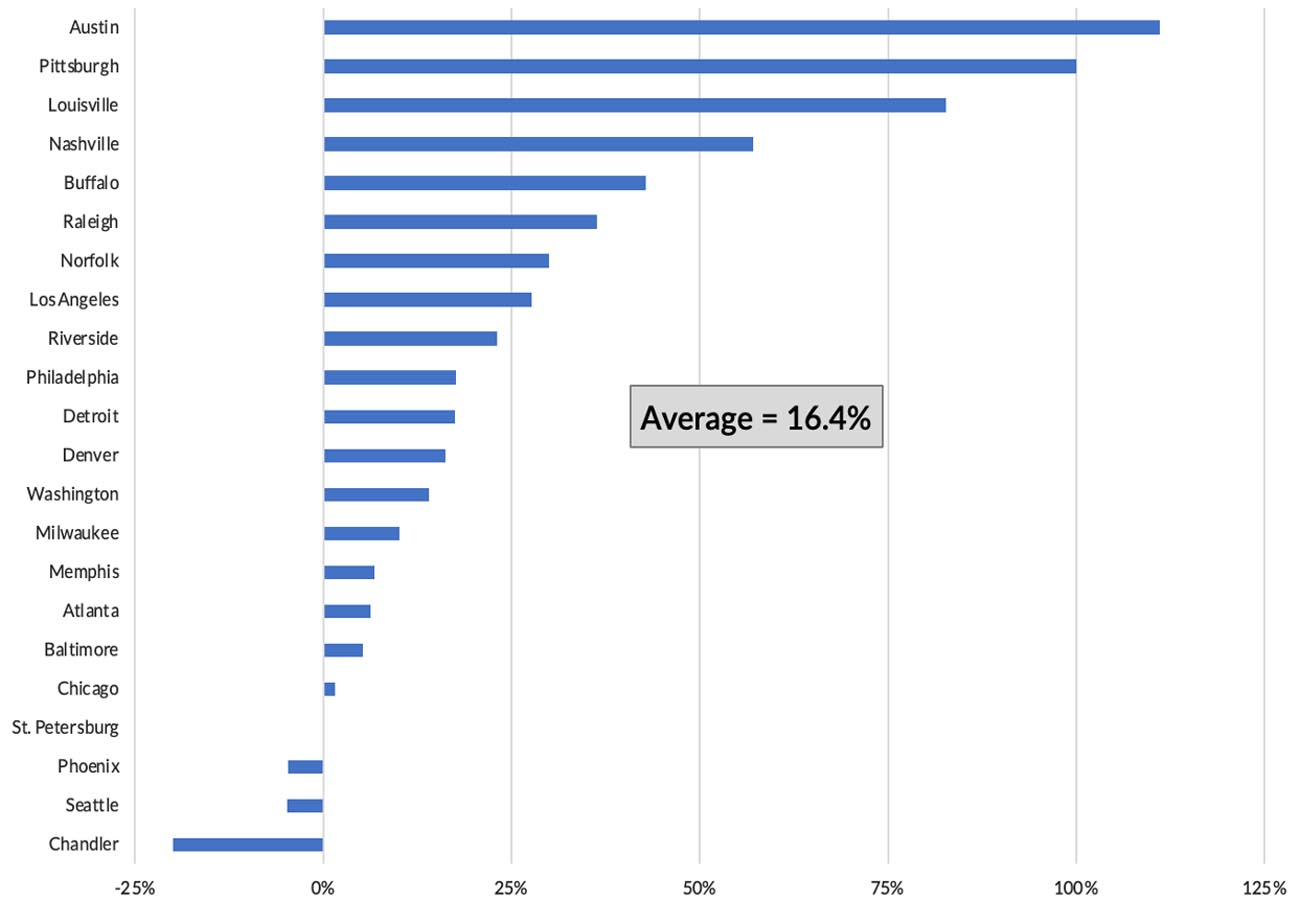

- Violent crime, particularly homicide, spiked during the pandemic. According to the most recent Council report, homicides in 29 major American cities rose by 16% from January through June compared to the first half of 2020 and by 42% compared to same period in 2019. This followed a 30% increase in murder in 2020 compared to the year before. While these are sizeable increases, the rate of increase slowed from the first to the second quarter of 2021. Nonfatal assaults also increased, while robbery, burglary, larceny, and drug offenses declined.

Average Homicide Rate, January 2018 – June 2021

- Community gun violence drove the increase in violence. Homicides increased mostly due to community gun violence, i.e. violence in community settings that involved firearms. In addition, these increases occurred in communities of color suffering from high rates of concentrated poverty where crime and violence were already prevalent. There is little evidence or data indicating that violence is spreading beyond such communities to other areas.

- Violent crime increased in most U.S. cities, but not in other countries. During the pandemic, a large majority of cities in the U.S. experienced a significant increase in homicides, although the magnitude of that increase varied substantially. This suggests that national factors drove the increase, but that certain cities and even communities within those cities may have been especially vulnerable to such factors. Violent crime rates did not increase in other countries.

Percentage Change in Homicide in 22 Cities, January-June 2020 to January-June 2021

- Multiple factors, operating simultaneously, converged to increase violence. There is no single explanation for why community gun violence escalated dramatically during the pandemic. What we do know is that a variety of new and shifting factors combined to create a “perfect storm” of circumstances pushing homicides higher. Several of these factors are discussed below.

Leading Explanations

- Based upon the research and data currently available, it is impossible to identify with precision or certainty the number of factors driving violence and their relative importance, or to disentangle their interacting effects.

- The coronavirus pandemic contributed to the increase in violence, but it is unclear exactly how.Criminological theories suggest different, even contradictory, responses to the pandemic. Routine activities theorypredicts that when opportunities for crime decline (e.g., when there is limited interaction between people, as occurred during lockdowns), crime will decline. Strain theory, however, suggests that when individuals are placed under strain they are more likely to make poor decisions, including committing crimes. To date, it has been difficult to disaggregate the complex interactions between the pandemic and crime.

- The pandemic halted the provision of critical services for those at the highest risk for violence. Working Group members reported that the pandemic temporarily prevented service and treatment providers, as well as law enforcement, from engaging those at the highest risk for violence, causing increased instability among this already fragile population. Moving forward, providers must be better supported to withstand temporary shocks and avoid interruption of critical violence prevention services.

- A sharp increase in violence followed the murder of George Floyd in late May 2020, but it is unclear exactly why. There is evidence that “de-policing” (i.e., a reduction in discretionary police activity such as stops and searches) was associated with the rise in violence. There is also evidence suggesting that “de-legitimization” (i.e., reduced confidence in police, particularly in poor communities of color) contributed by reducing reliance on public authorities to resolve conflicts. Both mechanisms likely played a role in rising violence.

- Firearm purchases rose dramatically during the pandemic, but their impact on recent violence is questionable. During the pandemic, sales of firearms increased substantially. In 2020, Americans purchased approximately 23 million guns – a 64% increase from the year before. Nevertheless, recent research suggests that these purchases were not associated with increases in gun violence, at least not in the near term. This is likely because the average “time to crime” for legally purchased firearms is approximately five to seven years.

- A surge in illegal carrying of firearms, however, may have been more impactful. In Chicago and elsewhere, police recovered more illegal guns even as they made fewer arrests, suggesting that more individuals were carrying firearms even when legally prohibited from doing so. Working Group members from law enforcement expressed concern about the trend, and noted an atmosphere of impunity for such offenses.

- Drug overdoses surged during the pandemic, but the impact of this increase on violence is uncertain. In 2020, there were more than 29,000 overdose deaths – due mostly to opioids – in the U.S. This represents a 29% increasefrom the year before. One study finds an association between opioid death rates and homicide rates between 2009 and 2015, but further research is needed to confirm any connection.

- Releases from jail increased dramatically during the pandemic, but there is little evidence those releases or other criminal justice reforms significantly contributed to violent crime rates. In order to minimize the spread of COVID-19, jurisdictions thinned jail populations by approximately one third in the immediate aftermath of federal and state declarations of emergency (prison populations declined significantly less). The majority of these releases occurred before violent crime rates began spiking, and rebooking rates for those released were lower than average, suggesting that these releases did not have a significant impact on public safety. In addition, there is little evidence currently supporting the claim that changes to bail processes, “defunding” police departments, or other criminal justice reforms are driving crime increases. This is because such increases are happening in the majority of U.S. jurisdictions, including those that have not enacted such reforms. Working Group members remain interested, however, in exploring how changes to bail and other criminal justice practices and policies have affected those at the highest risk for gun violence.

What To Do

- Community gun violence is driving the current increase in violent crime generally, and homicide in particular. Therefore, policymakers and practitioners should focus their efforts on addressing this particular form of violence, especially in the locations and among the people most likely to commit and be victims of it.

- Efforts to engage those at the highest risk of committing community gun violence must be renewed and strengthened, with additional funding and technical assistance for the governmental and non-governmental institutions performing the work.

- Additional research is needed to better understand the underlying dynamics of the recent rise in violent crime and to more effectively pinpoint which factors were most responsible.

Putting Violent Crime in Context

The mission of the Working Group is to save lives by providing guidance concerning violent crime that is timely, relevant, reliable, and accessible. Nevertheless, Working Group members believe such guidance must be placed in a broader social, political, and historical context.

What We Know

High levels of crime, violent and otherwise, are produced by structural factors, such as poverty, inequality, and systemic racism. While the Working Group will generally focus on providing short- and medium-term responses to violent crime, members agreed that leaders at all levels of government must also work to find long-term solutions to the persistent structural challenges that allow violence to proliferate in poor communities.

In America’s cities, crime, violence, and concentrated poverty are often found together. In disadvantaged urban neighborhoods, a combination of inadequate housing, poor schooling, and limited access to economic opportunities, transportation, and government services put communities under tremendous strain. Such strain, especially when it persists over long periods, produces crime and violence.

As sociologist Patrick Sharkey has noted, the cumulative effect of living in concentrated poverty over generations is severe. In his book Stuck in Place, Sharkey shows that 70 percent of Black Americans living in poor communities today are from families who lived in those same communities 50 years ago, and that many of these Americans suffer from multiple forms of intergenerational trauma.

These conditions were not created by accident. Exclusionary policies such as redlining, blockbusting, restrictive covenants, and other historic forms of discrimination were put into place by policymakers seeking to prevent Black people and other minority groups from moving freely and mixing with their fellow citizens. Once communities of color were separated from broader society, leaders systematically disinvested from them. Such discrimination spanned generations and, along with deindustrialization and outmigration, produced high rates of concentrated poverty that created fertile ground for crime and violence to thrive.

More than fifty years ago, the Kerner Commission, in response to widespread protests and rioting during the summer of 1967, identified “pervasive discrimination and segregation” as a root cause of the unrest and recommended major investments in housing, education, employment, and social services to remedy severe racial and economic disparities. Unfortunately, a strong backlash to the Commission’s findings led them to be largely ignored. Nearly 50 years later, inequalities persist, with Black and Latino people twice as likely as White people to live in poverty. In addition, Black people are killed at eight times the rate of their White counterparts, and Latinos are killed at almost double the rate of White people.

What To Do

Moving forward, the Working Group will focus on solutions that provide relief quickly to communities suffering from high rates of crime and violence. Violent crime is produced by structural factors such as concentrated poverty, but it also perpetuates them. A large body of research identifies exposure to violence as a “central mechanism” for limiting the life chances of poor Americans. That said, Working Group members believe that the broader context of violent crime must be taken fully into account and addressed in order for violence-reduction benefits to be sustained. To achieve that goal, leaders must pair targeted interventions to prevent violence with wider investments to address the root causes of such crime.